His canvases are grouped in irregular patterns to create a whole, composed of irregularities and conforming to a rectilinear format at their edges. At first glance, I am reminded of the black and white sculptures in the work of Jean Dubuffet; it is as if Bernáth has picked up where Dubuffet left off and brought us into a contemporary context with his recent work. One could compare this underlying lineage to passing on the Olympic torch to light the flame of a new year’s games.

Dániel Bernáth shared a video with me that explains his process; he splits the wood at his studio in the countryside and allows the lines of the grain to determine the shapes. The years of a tree’s life determine the essence of each part in the whole of his work. Smoothed and painted, the works are fitted together, a matrix to be used only once, a plotting of shapes, the organization of which becomes satisfying as each part has its very unique place. A metaphor is born from the seemingly arbitrary splitting of wood and the fitting of things back together again in new connections.

Artist Dániel Bernáth with gallery director Ani Molnár, photo credit: Anne Murray

“When applying impact on the cross section of the stretcher's slats, they crack through their weakest part. The stroke itself as an action is also a defining moment of creation. An irreversible process that takes one second. The older a tree is, the greater tension is generated between its decades and this certain second. It is a rupture in an ontological sense too, something irreversible happens, which is exciting to me. By splitting and reassembling the wooden elements, I create pictorial masses and proportions within the composition, adapting to the shapes rippling along the cramps, while arbitrarily forcing them into a new structure in search of new proportions for the elements,” Bernáth explains.

I notice Bernáth’s works seem to hold two simultaneous truths: one of a finite refined and defined color relationship within a flat plane, and the other a craquelure pattern governed by unseen truths, as tectonic plates, shifting and following unique shapes and order. The color relationships and applications in these works seem to appear more as a pure color or light — an aura — or as a glowing element of a neon light might be presented in paint.

Dániel Bernáth: Mountain Mama No. 47, 2020, wood, canvas, acrylic, 170x150 cm,

courtesy of Ani Molnár Gallery, Photo credit: Anne Murray

I asked Bernáth about the color relationships and presentations: “I compared the natural silhouette of the elements of the composition with the toolbox of industrial technical painting and its synthetic and 'romantic' color tones to make the optical and content tension even more pronounced on the surfaces.”

I thought about the uniqueness of these paintings, their aura created through the individual experience of each tree and the splitting of pieces along fault lines, which naturally led me to ask Bernáth about Walter Benjamin and his writings, specifically The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. “Are you bringing individualism and chance to minimalistic representations/explorations as if you are naming something, identifying it uniquely, creating a work as a person?”, I queried via email.

Curator Lili Boros with artist Dániel Bernáth, (artworks by Balázs Csizik in the background)

Photo credit: Anne Murray

“My main interest is the image itself, as an object and an idea, a historical and abstract formation. My interest basically revolves around the image as a possible identity. Due to the 'iconic' nature of non-technical images, we treat them differently than any other visual format in the world. My artistic work is based on these perception categories associated with each medium and the art history clichés related to them. In this sense, Walter Benjamin's thoughts are very important to me. The uniqueness of the works stems from the crooked and cramped silhouette of their stretcher, as nature does not produce two identical shapes and forms. Hence the unique, unrepeatable presence of paintings, which allows us to imagine an object as a function with a kind of identity. This is precisely why I wanted to strive for impersonality in the works, so that as many elements of the images as possible are determined by influences and factors that are beyond my creative intent,” responds Bernáth with an exquisite surety.

The works are beautifully paired with the art of Balázs Csizik, who works with photography, sculpture, and installation. (see my next interview with Balázs Csizik in a subsequent article). I wondered about the curator of the exhibition, Lili Boros, and the title Geotaxis: “The term ’geotaxis’ is used in biology, refers to the movement of a cell or microorganism, determined by gravity, towards the earth, a place or matter. In other words: moving towards (concrete physical) boundaries (Bernáth) or shifting and moving points of view (Csizik).”

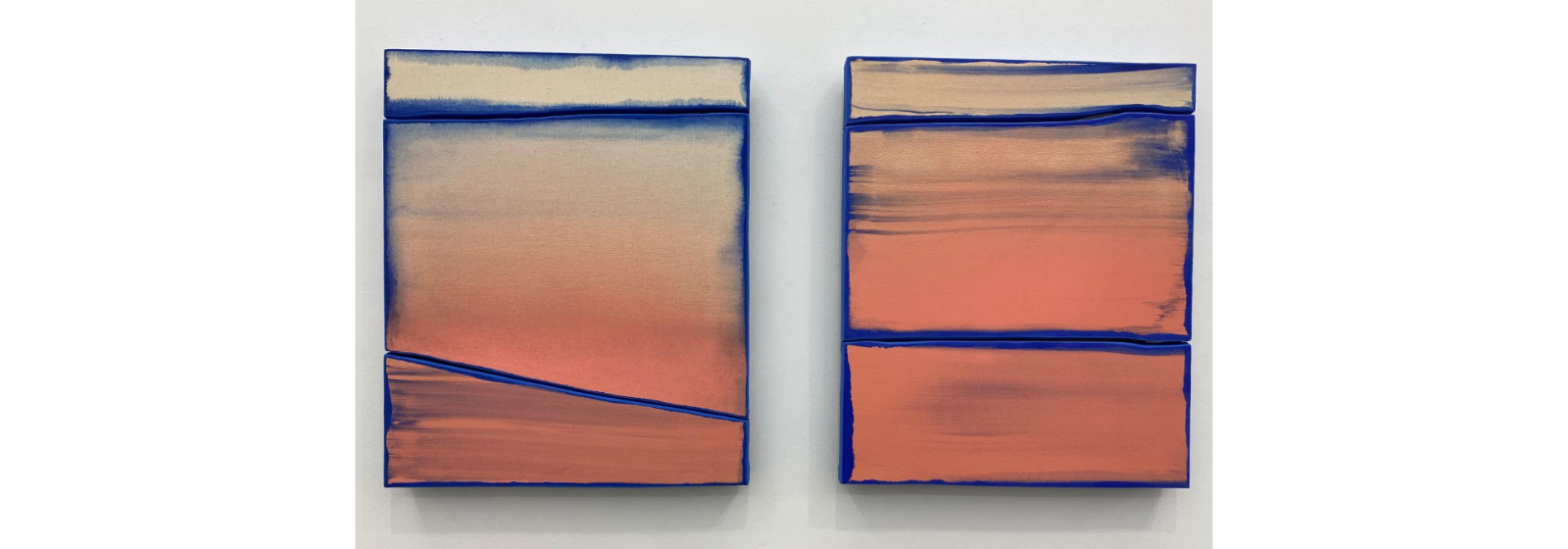

Dániel Bernáth: Mountain Mama No. 44 and 42, 2020, wood, canvas, acrylic, 50x42 cm each, courtesy

of Ani Molnár Gallery, Photo credit: Anne Murray

The title, Geotaxis, and its meaning, poetically grounds us, puts us back into nature, the elements, and our connections on a cellular level. I wondered how Boros contextualized this exhibition, particularly in relation to our current global crisis and in choosing particular works by these two artists. “As far as I know the crisis began not now, we are in the middle of this process. The economic disaster is a current topic in philosophical and artistic interests and discussions of our days. Because of that and due to the reason that every human person is involved in this issue, I see a trend in contemporary art, which has a ‘romantic’ character, and which thematicizes not only the tradition but the correlation between traditions. Humanity and its surrounding always gives the possibility to interpret and understand ourselves and our current situation. From this point of view I tried to choose those works which are self-reflected and therefore related to our current global crisis.”

The works are on display at Ani Molnár Gallery in Budapest until October 10, 2020.