Mozenter’s website offers a rich grouping of the progression of her ideas and research over the last few decades, with accompanying texts written as beautifully as any poetry; they are thoughtful descriptions of her experience as an artist and a witness to life and its progression within the interior landscape of thought. I first encountered her work while she was a professor at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, in the nineties and was especially drawn to her soap pieces. “In the early 90s I made a body of work titled Preserves, consisting primarily of nuts and soap coated with beeswax and sometimes wound with thread and layers of thin paper. I am, and have always been, fierce about preserving myself, my imagination, my individuality.” It is clear that Mozenter has a bold and decisive approach, a testimony to what it takes to survive in the New York art scene.

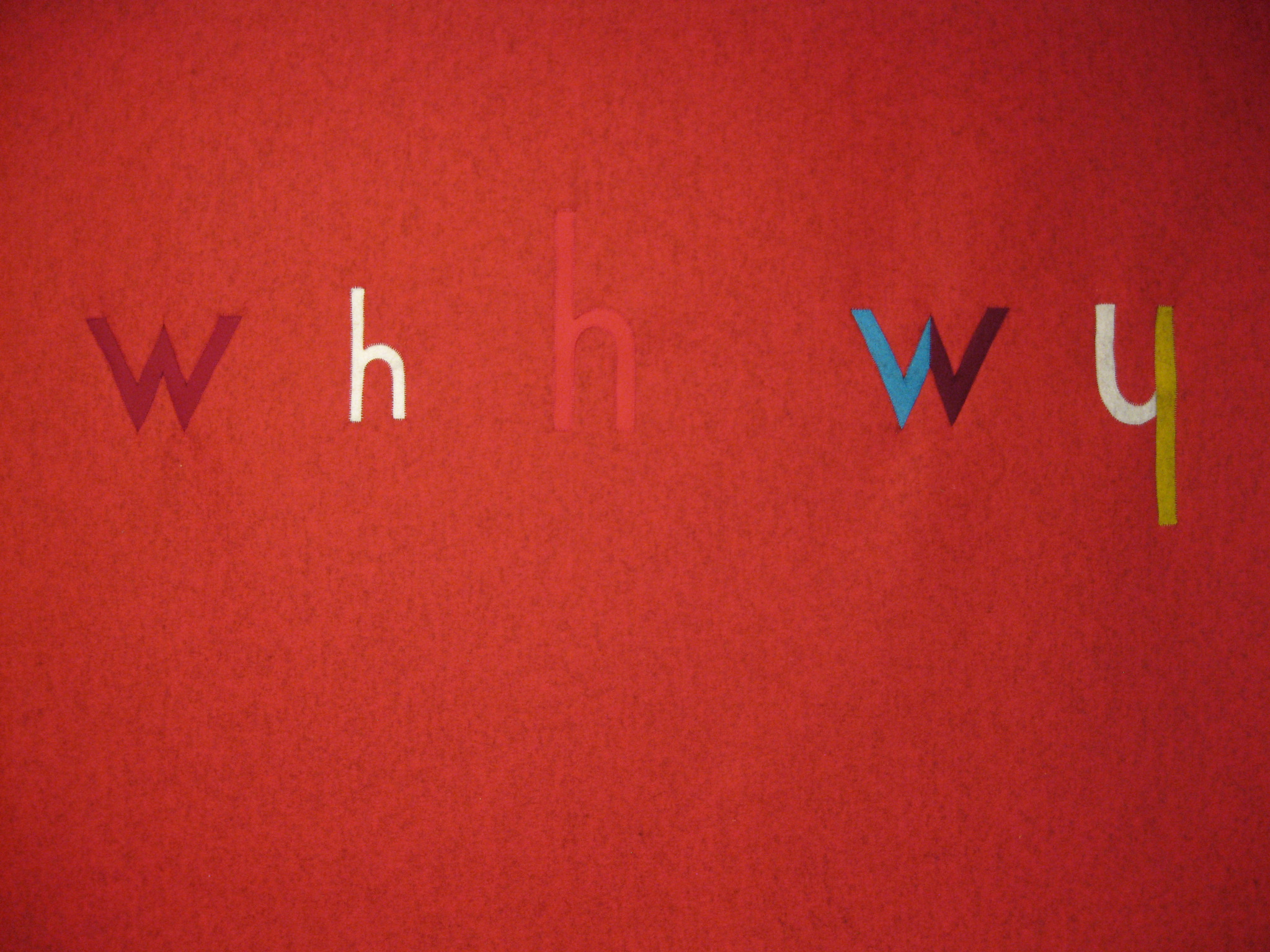

Detail of Red (2016), Cyrilla Mozenter. Industrial wool felt hand stitched with silk thread. Photo by the artist.

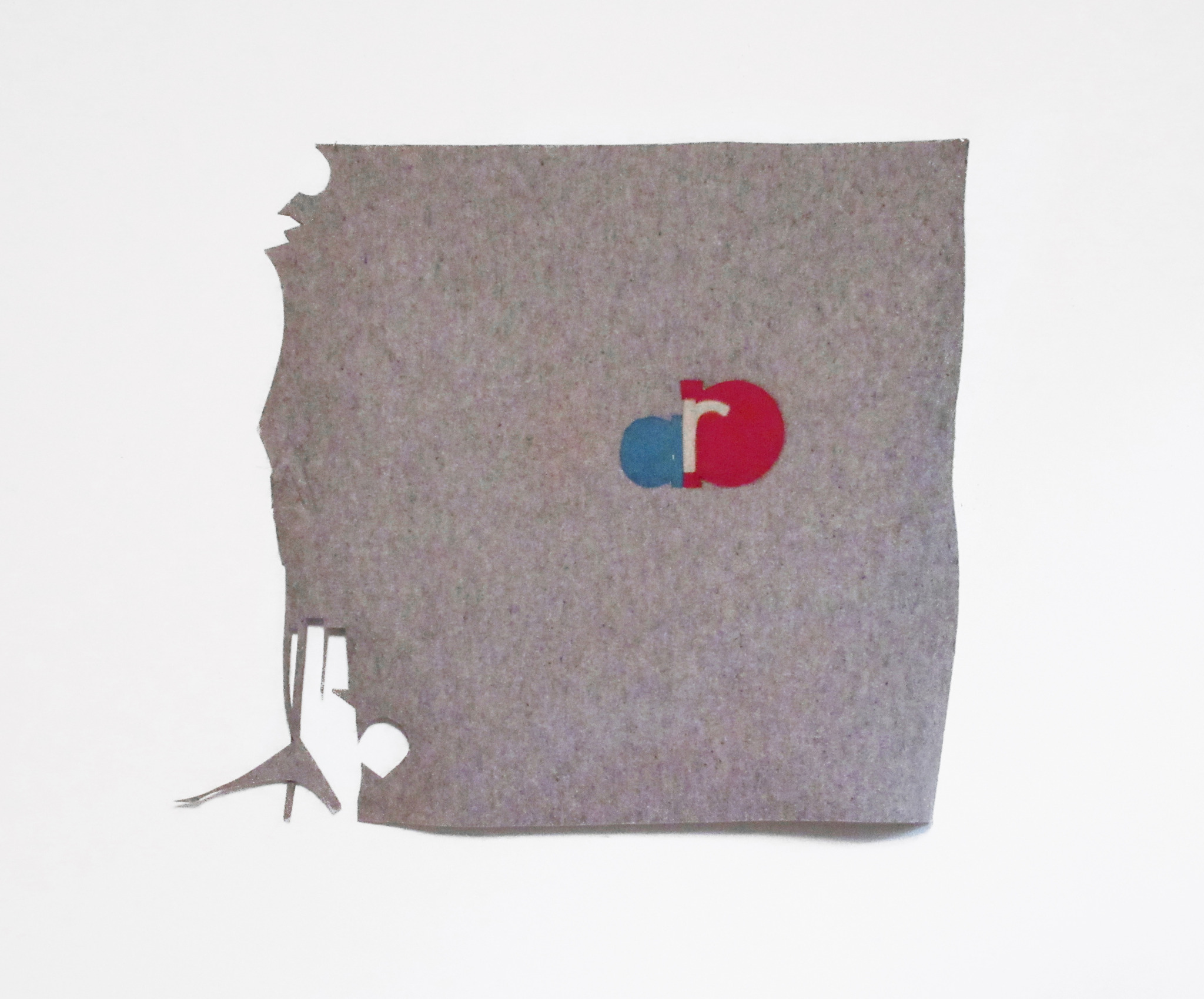

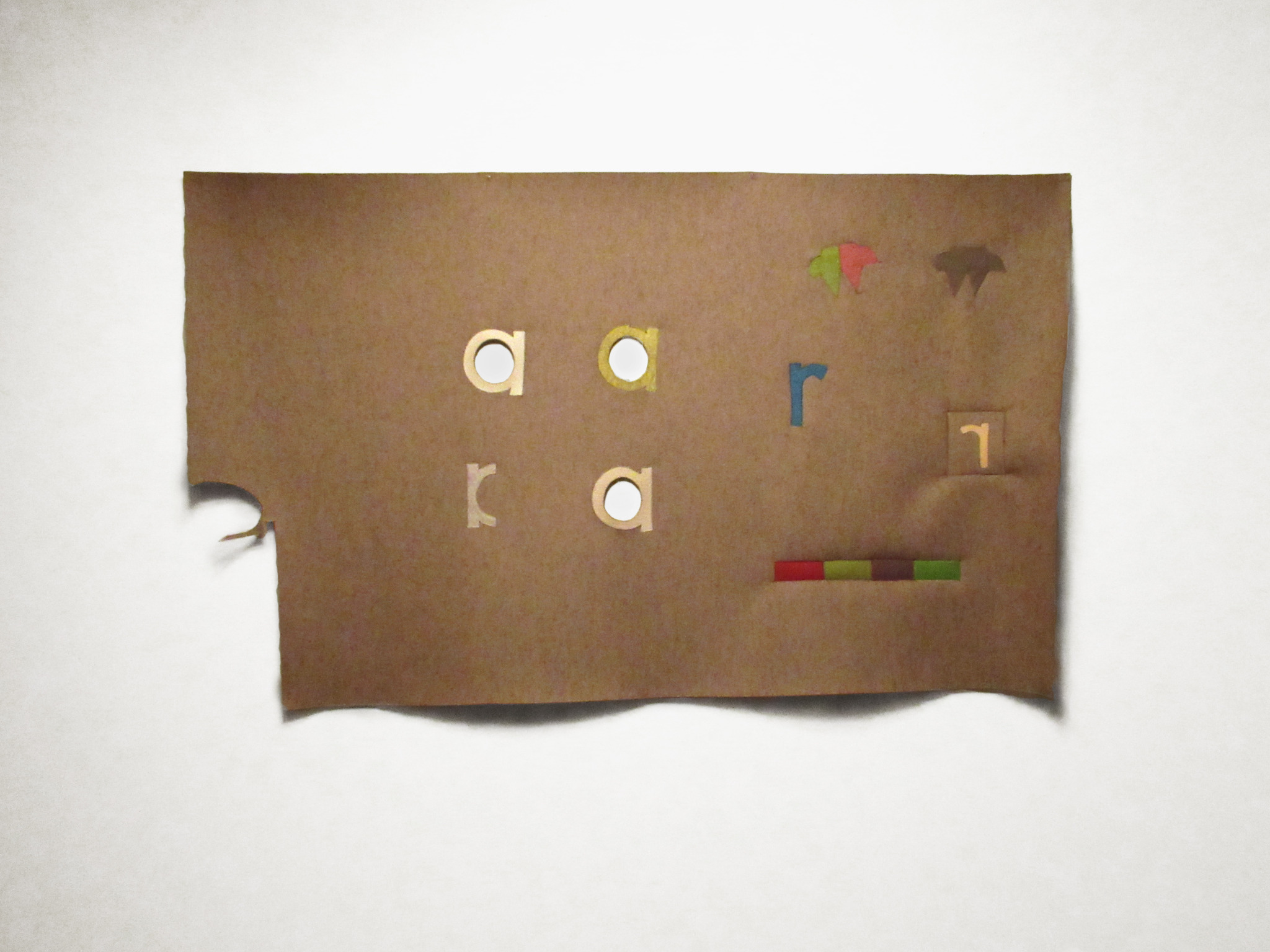

My notes as I read her work, both visually and literally, become an abstract stream of consciousness, a witness to how her perceptions are multidimensional and surpass contemporaneity. Her sculptures and drawings bring together small essences - potent and privileged, private but inviting. Working with felt, silk thread, paper with pencil, gouache and cut-and-pasted paper most recently, and soap, seeds, and paper in the past, her sculptures, drawings, and wall pieces have a curious nature that recall her artistic spirit like some mysterious bird who brings together pieces of signifiers, letters that have been sliced, truncated, turned upside down. In essence, they are gatherings, spotting and identifying what is of interest in a direct and subliminal way, creating new arrangements to bring their shapes into focus. Carefully cut letters are inlaid into felt that has preserved the hazarded path of scissors, almost perfect rectangles with dangling ends where one imagines a letter was formed by a slicing action. Metaphorically, they appear less scarred than repaired or replaced, recalling for me the works on repair by Kader Attia in an abstract way, and their references to the repairs of wooden sculptures from different countries in Africa, which are oddly incongruous, but satisfying in their honesty.

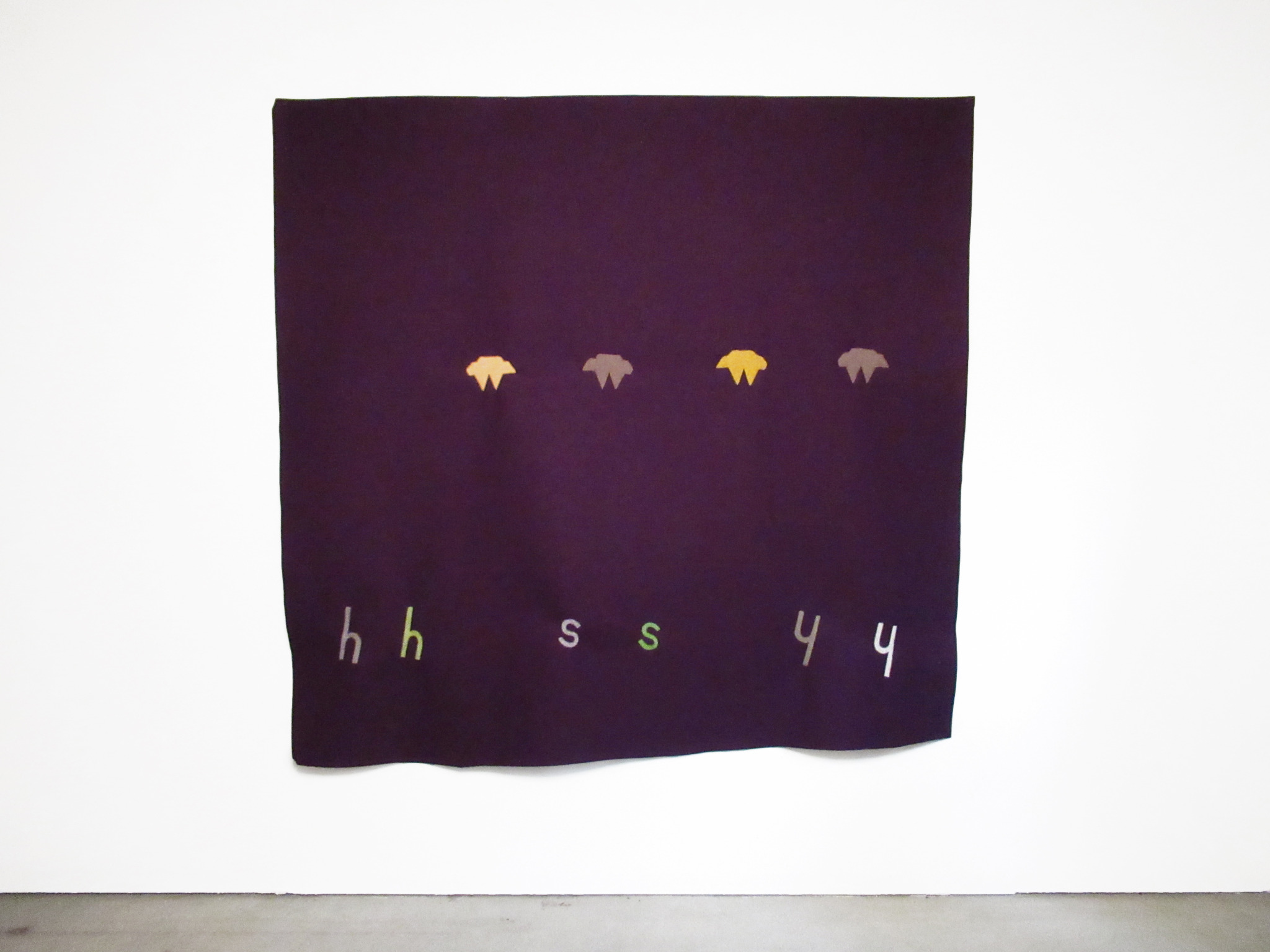

Deka (aubergine) (2018), Cyrilla Mozenter. Industrial wool felt hand stitched with silk thread. Photo by the artist.

Detail of Deka (aubergine) (2018), Cyrilla Mozenter. Industrial wool felt hand stitched with silk thread. Photo by the artist.

I asked her about the concentration of semiotics disambiguated and recontextualized, in a field of colored felt, and how these deliberate choices relate to her beginnings as an artist. She responded with due diligence, “My father was outed for organizing government workers during the McCarthy era. I was born, less than one month later, into an atmosphere of anxiety, uncertainty, fear, sadness, and isolation. I was motivated to find my own stability, my own ground, to find what I could trust, what was true. I enjoyed my kinesthetic and tactile sensations, the beauty of colors, the exquisitely subtle tones of my grandfather's photographs. I enjoyed, too, a sense of confidence, happiness, and power in 'translating' my experience of the world, with materials, into my own language of form—my true. I was never not an artist.”

Indeed her work is a graphically rich and textured experience; the tactile is a voice unheard, but felt. The presence of the materials give rise to their own semiotic voices, the felt, a “compressed chaos” as she eloquently describes it.

Known to find inspiration from the writings of Gertrude Stein, she extrapolates from this process, “I have no routine way of using Gertrude Stein's words. Her writing strikes me as true. I love the physicality of her language and how delicious it is to speak. Her writing is playful and ridiculous. It puts me at ease. I have written her words and phrases primarily in works on paper at various stages in the process, and I have used her words as titles.”

Some say some say some say so (2018), Cyrilla Mozenter. Industrial wool felt hand stitched with silk thread. Photo by the artist.

Unfamiliar with much of Stein’s work, I chose to read the libretto, Four Saints in Three Acts, which, with the musical score of Virgil Thomson, formed the eponymous opera, first performed with an all African-American cast in 1934 at the Wadsworth Atheneum (introducing the first solo show of Pablo Picasso in the United States). I had vaguely heard of it when Mozenter mentioned it and then remembered an exhibition I had seen at The Photographer’s Gallery in London a few years ago, which had some photos from the original performance. Stein’s writing uses repetition and evolution of phrases, which are almost musical; one can feel time in multiple dimensions. There is a clear visual relationship to this concept of overlapping time and flattening space in Mozenter’s works with letters and shapes emerging, dissolving, and crossing paths as if the compressed chaos of the felt was a nebulous form, a storm cloud composed on flat planes.

See Why (2019), Cyrilla Mozenter. Industrial wool felt hand stitched with silk thread. Photo by the artist.

Mozenter speaks of her process, “I work improvisationally. I do not plan. I buy colors of felt on impulse with no particular outcome in mind. Sometimes I buy colors I hate— just for the hell of it. I generally use the hated colors immediately. I'm motivated by the challenge.”

It is captivating to see how she manages this discord with the colors, for they hold so well together, stitched in marquetry, balancing compositional relationships with defined elegance. “The stitching creates tensions that cause unpredictable distortions on both sides of the seam. Both sides resist. Neither side 'likes' it. Both are transformed in the joining as the work takes on subtle dimensionalities. The felt, no longer flat, is alive. This coming into aliveness is beautiful—a miracle. Every time.” Indeed, the aliveness of the tension between both sides, and its beauty, begs us to consider the unrest globally and more locally in the United States and imagine perhaps other forms of interaction, other shapes to create and examine our differences and accords.

island r (2012), Cyrilla Mozenter. Pencil on rock, industrial wool felt hand stitched with silk thread. Photo by the artist.

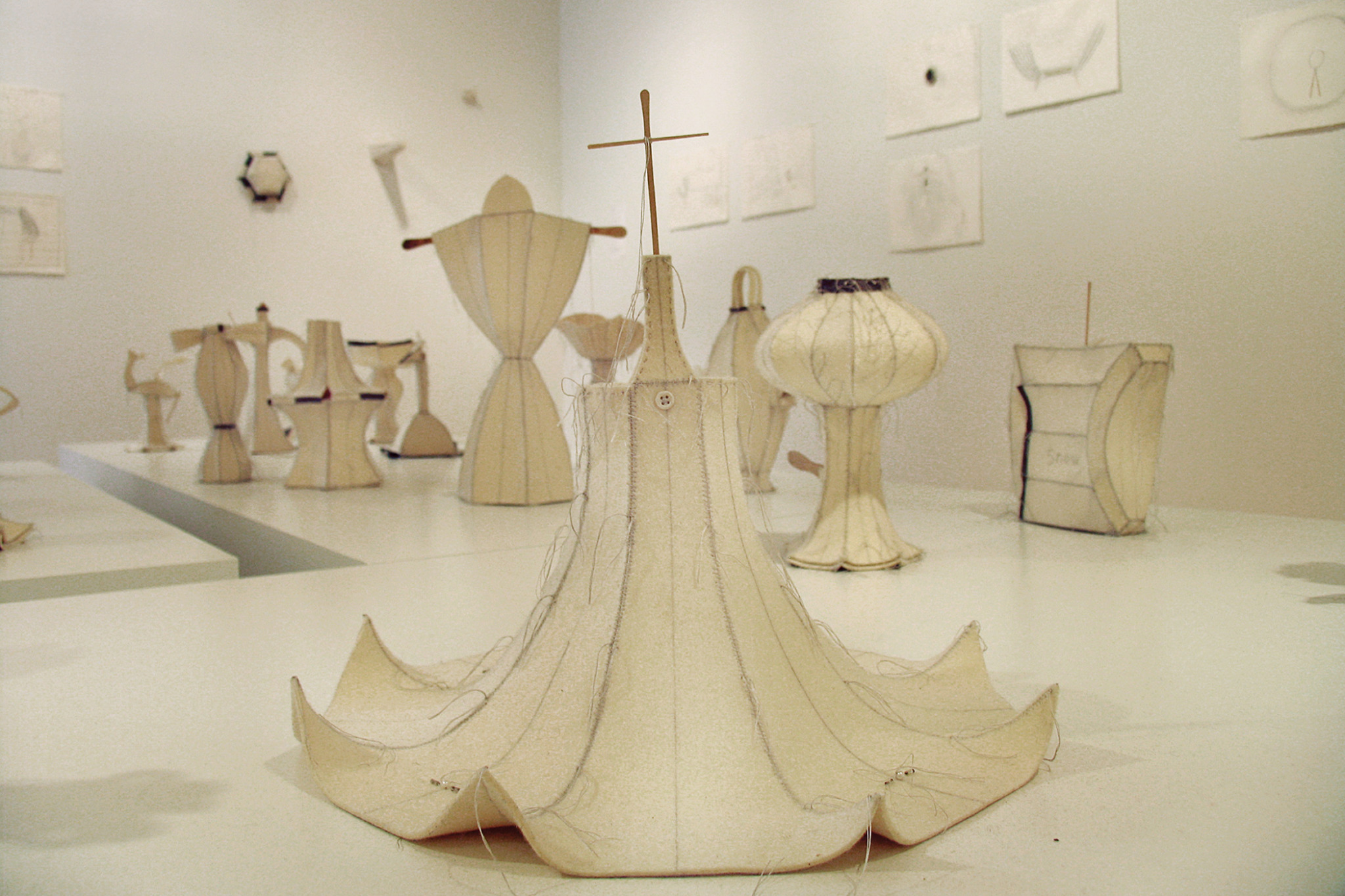

More saints seen (2005), Installation view 1, Cyrilla Mozenter. Sculpture and drawings: wool felt, paper, pencil, silk thread, tooth picks, buttons, pearls, beads. Photo by the artist.

Her works sometimes have the same shapes, but they change languages with fluency, as musical scores that play in a different key or offset an established balance with disharmonious tones, becoming oddly harmonic in their originality. I think of contronyms. I asked how she was affected by the global pandemic, if it entered into her work and about the work funded by the Guggenheim fellowship, she received this year. “I was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship early in the pandemic. Chance offered a grey, slightly irregular, elongated felt rectangle with two small triangles extending from one side. I experienced an impulse to cut and stitch an orange letter 'c' within it. It required companions of different colors of felt. I began to think of them as pennants or banners. A silent celebration of the Fellowship, 'c' being the first letter of my first name. Though it occurred to me later that 'c' is also the first letter of covid, it is a note, a musical key, and sounds like sea and see. The rectangles made visual sense in groupings of four. (Bars in a musical score?) Other shapes 'of my acquaintance' have entered and some are simply two colors of felt joined at a horizontal seam. While this work goes slowly, I have by now nearly filled my studio walls. It is an on-going installation,” responds Mozenter.

The Woolly Rhino and Its Shadow (2013), Cyrilla Mozenter. Pencil on archival manila file folder, archival corrugated cardboard, cut-and-pasted handmade Japanese mending paper. Photo by the artist.

I remember as a child being fascinated by the ligature representation of the lower case æ grapheme called ash. I see her representations of single and sliced letters as relatable in both an intuitive way and in the piecing together - a metacognitive process of learning, when associations are more distinct, as a child who has limited life history and can imagine other possibilities for these signifiers with a fluidity of spirit. The relationship between precision and tactility reminds me of creatures in the sea with both a form and a mobility which allows for the change of shape. I wondered if there were beings that particularly interested her in terms of their attributes. “There have been periods in which the image of the polar bear or cat-rabbit predominate. I am interested in my own creature-ness. The images I make are pictograms. They co-exist in my work with letters of the alphabet and other pictogram-like shapes. I see no reason to segregate different language systems. I am making my own.” She describes how this relates to her workspace as well, “Through my studio windows I see a wooded area. I see fox. Deer abound. We see and hear each other. I love to watch them move.”

Her recent collaborative projects include Octave (published by anmoc press, Seoul, South Korea) which is a bilingual book including her photographs of work with felt and paper alongside gelatin silver prints by artist Philip Perkis. Her words to sum up her process act as a mantra for us in the time of Covid-19, “I enjoy embracing, being thrilled by, what had repelled me or what I thought I might not be able to manage.” Her work brings hope in a time of great chaos. Let’s work to compress this chaos and find some balance.