The 57th edition of the Venice Biennale is set at a time when there is much more at stake than the purely celebrative thematic chosen by curator Christine Macel: “Viva Arte Viva”. The wide scope of the Biennale’s title makes for a hugely varied offering, and whilst the last edition of the event was decidedly political — curator Okwui Enwezor selected the theme “All The World’s Futures” featuring daily readings of Das Kapital and artwork addressing famine, mass incarceration and ecology — there is nonetheless a gravitational draw towards the political and an implicit questioning of the role of art in fraught times. This is translated in an albeit less obvious way; Macel’s biennale provides a space for reflection in many different forms.

At the American pavilion, superstar artist Mark Bradford (known for his charitable work, using profits from his artwork to support the associations Art & Practice and Rio Terà dei Pensieri — a charity which provides educational programs to detainees in Venice) makes an appeal to the American president on behalf of discriminated against peoples. “Like much of Bradford’s work, the installation addresses the discrimination and violence against black, gay, and other marginalized bodies,” explains the press material. His overtly political work is manifested in the form of mountainous collages made from scrap and waste — a metaphor for those who are so frequently discarded or overlooked.

At the entrance to the Giardini, the Swiss Pavilion is marked by the absence of Alberto Giacometti, that is to say, artist Carol Bove is exhibiting seven sculptures, reminiscent and in response to the work created by Giacometti at the end of his life. Alongside Bove, American-Swiss duo Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler are showing Flora, a video installation following the life of Flora Mayo, who studied in Paris during the 1920s and was Giacometti’s mistress. Together with Bust — representing Giacometti and recreated by the two artist starting from a lost work by Mayo — the video has a unique resonance in the contemporary context in its discourse with an absent Giacometti. The pavilion was constructed by the artist’s brother Bruno Giacometti in 1952, yet the artist resolutely refused to participate in the Swiss presentation, for he did not wish to belong to a state — an affirmation that takes on renewed relevance in 2017.

Moataz Nasr's video work in the Pavilion of Egypt, La Biennale di Venezia, May 2017 (Photo by Oak Taylor-Smith)

Elsewhere, the Egyptian pavilion is showing the film Mountain by artist Moataz Nasr, projected across several screens simultaneously. Halfway between fantastical novel and ancient fable, the work recounts the opportunity represented by the possibility of opening up, the distance created by fear, the necessary hope of progress, and the utopia of happiness.

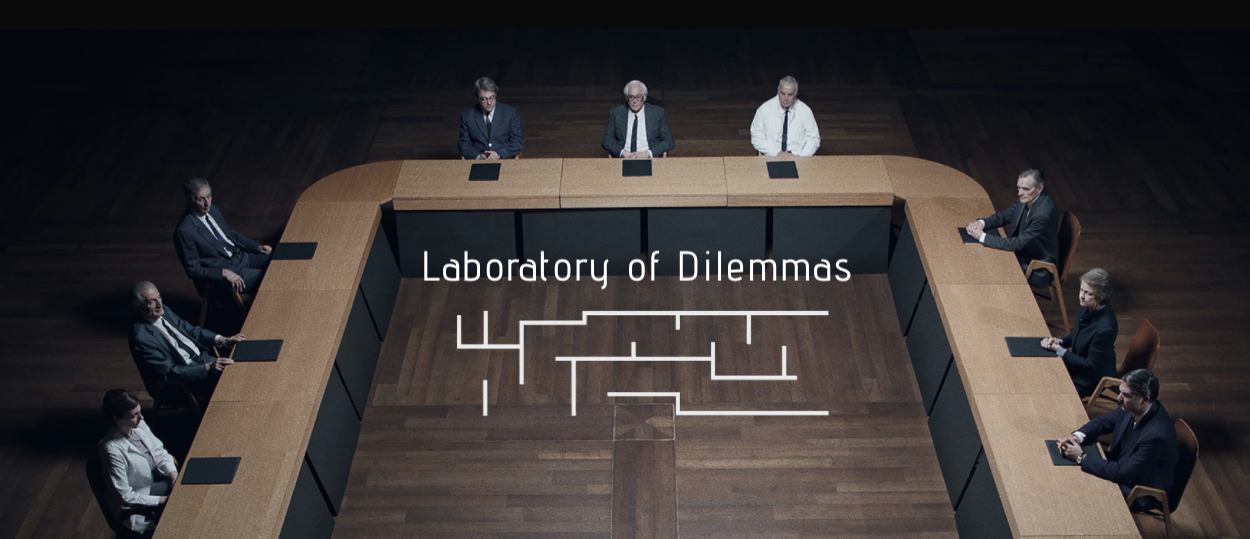

The Greek presentation presents a more advanced problematic, where the onus is on action. Plunged into the heart of a labyrinth, visitors follow step by step a scientific experiment that has been reconstructed and relayed by artists George Drivas. The exhibition traces the experiment led by a researcher during the 1960s on the possibility of hepatitis resistant cells which are only able to exist in cohabitation with pre-cultivated cells. Through a series of short videos and the accompanying notes of an unnamed filmmaker, the work looks at an ethical issue which, through the cold world of eugenics, presents a subtle parallel with the current wave of migration.

Still from Laboratory of Dilemmas by artist George Drivas at the Greek Pavilion

Whilst the national pavilions — especially in the Giardini — have embraced Macel’s theme of Viva Arte Viva in a largely original and incisive way, the curator’s group exhibition at Venice’s Arsenale falls flat. In asking artists to “reinvent the world” rather than to change it, without closing themselves into a pattern of denunciation, the exhibition does not necessarily achieve the life-affirming spirit that it looks to evoke.

The overall stand out pavilion of the week, evidenced by hour-long queues and almost universal praise from the international press, was the German presentation. Anne Imhof’s new work Faust an all encompassing long-duration performance piece is interesting to view in the context of Macel’s thematic. The starkness of the surroundings, the violence that the sculptural objects evoke — knives, mortuary hoses and ropes — might seem to allude to a nihilistic allegory for apathy and angst that the capitalist machine induces, yet the hordes of visitors bustling to get through the pavilion doors don’t seem to be the result of a morbid curiosity, there is instead an intimacy and an emotion that emanates from the space. “In my opinion Angst ⦋a recent work by Imhof that toured Basel, Berlin and Montréal⦌ is just as life-affirming as it is critical. And I don’t think people would have been so drawn to it if it wasn’t,” says performer Eliza Douglas in the exhibition catalogue. Surely this is the attitude that Viva Arte Viva looks to express.